A Massachusetts resident, Faustina began working on her college applications last August. In the beginning, the process was going well. However, as she began receiving acceptance letters and financial aid award letters, things became difficult. As an undocumented student, Faustina did not have a permanent residency card, which most colleges need in order to provide financial aid. Unwavering in her efforts to pursue a higher education, Faustina hoped to receive financial support from private institutions but, often, they could not meet her need.

A Massachusetts resident, Faustina began working on her college applications last August. In the beginning, the process was going well. However, as she began receiving acceptance letters and financial aid award letters, things became difficult. As an undocumented student, Faustina did not have a permanent residency card, which most colleges need in order to provide financial aid. Unwavering in her efforts to pursue a higher education, Faustina hoped to receive financial support from private institutions but, often, they could not meet her need.

As a Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) beneficiary, Faustina was ineligible for federal financial aid and, in most cases, state financial aid. Signed under the Obama administration, DACA grants a working permit to those who entered the U.S. before age 16, allowing students to enroll at institutions of higher education and join the military. In June 2017, the head of the Department of Homeland Security, John Kelly said that the DACA program would remain in effect, however, the long-term viability of the program remains unknown. While DACA allowed students like Faustina to come out of the shadows and apply to college, there is a long way to go to ensure that all academically qualified students have access to a quality and affordable higher education.

Undocumented students are ineligible for federal financial aid programs such as the Pell Grant, work study and government loans. As a result, these students rely almost exclusively on state support. Twenty states offer some form of financial aid to undocumented students, and most extend in-state tuition to undocumented students. Nationally, six states provide both in-state tuition and state financial aid. In New England, only two states offer financial support. Connecticut and Rhode Island extend in-state tuition to undocumented students if they meet certain criteria such as having attended a state high school for two or more years and graduated. Connecticut State Colleges and Universities President Mark Ojakian has taken a personal interest in the matter. “We support all students’ educational goals and dreams, not only because it is the right thing to do, but because investing in all our students improves the sustainability of our communities and the economic competitiveness of our state.”

Legislative action in New England

In Connecticut, the Higher Education and Employment Advancement committee, chaired by state Rep. Gregg Haddad (D-Mansfield), has introduced An Act Equalizing Access To Student-Generated Financial Aid, HB 7000. The bill allows students to have equal access to institutional financial aid regardless of immigration status. “Institutional financial aid” includes tuition waivers, tuition remissions, grants for educational expenses and student employment.

“The dreamers [undocumented students] themselves have been pushing this [legislation],” according to Haddad. Members of the CT Students for the Dream—an organization devoted to advocating for the rights of undocumented student—have played a crucial role in propelling the legislation, Haddad said. “They’re here, they have study-ins in the capital. They lobby extensively. They are unbelievably unafraid to identify themselves as undocumented residents.”

In addition to the students, “institutions in Connecticut have reacted so differently than institutions elsewhere” reported Haddad. For instance, in fall 2016, Eastern Connecticut State University admitted the first cohort of Opportunity Scholars. These scholars come from seven “locked-out” states—states that deny in-state tuition and, in some cases, bar undocumented students from enrolling—as well as 13 different countries. According to Eastern President Elsa Núñez, “no public funds are being used to support Eastern’s Dreamers, and no in-state students are being denied admission because of the program.” Instead, the 42 scholars in the cohort, in addition to five DACA students from Connecticut, are being funded by the Dream.US Scholarship program. In regard to continuing the program, “applications are already being accepted for fall 2017, and Eastern will likely enroll another 75 Opportunity Scholars,” according to Núñez.

There is a moral and an economic imperative to Connecticut’s support of undocumented students. The state faces a major budget deficit and struggles with the lack of an urban center that draws young people, putting the state’s vitality at risk. Therefore, Connecticut hopes to attract young people of all backgrounds.

While the leadership of the Connecticut State Colleges and Universities, and Eastern in particular, is admirable, more needs to be done at the legislative level to ensure that undocumented students have access to affordable education. HB 7000 is a step in the right direction but its future remains uncertain. The bill did not come to a vote during the 2017 legislative session but Haddad hopes to bring the bill back when the Legislature reconvenes. As Haddad continues to persist, Massachusetts state Sen. Sonia Chang-Diaz (D-2nd Suffolk District) hopes to pave new ground in her state.

Massachusetts has the highest number of DACA beneficiaries in the New England region with 7,258 individuals benefiting from the executive action. Still, Massachusetts has not passed legislation extending in-state tuition. Aiming to change the status quo, Chang-Diaz introduced An Act Providing Access To Higher Education For High School Graduates In The Commonwealth, S. 669. The bill extends in-state tuition and eligibility for state-funded financial assistance to any person who has attended high school in the Commonwealth for three or more years and has graduated from high school or has a General Equivalency Diploma (GED), with stipulations such as providing an individual taxpayer identification number (ITIN) in lieu of a social security number and signing an affidavit stating that the person has applied or will apply for citizenship or legal permanent residence within 120 days of eligibility. If passed, this bill would remove a major financial barrier to higher education for undocumented students, allowing them to enroll at a Massachusetts public institution with a more affordable price tag.

Survey results

To better understand undocumented students’ access to affordable higher education in the region, the New England Board of Higher Education (NEBHE) conducted a survey of undergraduate institutions in Connecticut, Massachusetts and Rhode Island. Out of 144 bachelor’s-degree granting institutions in these three states, 50 institutions responded to the survey. The majority of the survey respondents were 4-year private, nonprofit institutions followed by 2-year public and 4-year public institutions, respectively.

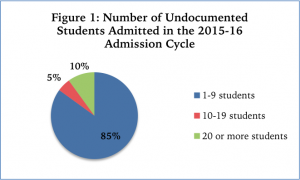

Of the institutions that responded, 72% reported admitting undocumented students in the 2015-16 admission cycle. Although because of the response rate, the results overall have no statistical significance, the responses reveal a broad range of attitudes toward undocumented students.

Figure 1: Number of Undocumented Students Reported Admitted in the 2015-16 Admission Cycle

Three 2-year public institutions admitted between 1-9 undocumented students in the 2015-16 admission cycle with one institution admitting more than 20 undocumented students. Given the financial challenges facing this group of students, this trend is not altogether surprising. Undocumented students tend to come from lower socioeconomic backgrounds and 2-year public institutions often provide a more affordable education than other alternatives. Comparatively, 11 4-year nonprofit private institutions admitted between 1-9 students and one reported admitting 10-19 students. Again, given the financial constraints facing this particular group of students, a 4-year nonprofit is more likely to offer them the financial support they need than a 4-year public institution.

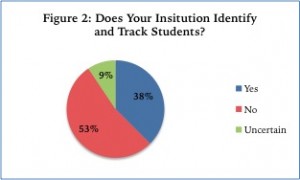

Figure 2: Does Your Institution Identify and Track Students?

Of the institutions that responded to the survey, the majority do not identify or track undocumented students (Figure 2). For institutions that do identify these students, they use a wide array of classifications ranging from “domestic student” to “non-eligible non-citizen” to being designated as a part of a “cohort.” One institution tracks these students as “DACA eligible” for in-state tuition purposes.

Forty-six percent of the institutions that answered the survey said that they provide resources specifically designated for undocumented students such as legal aid, student organizations focused on immigration and staff members whose mission is to support undocumented students. One institution formed an “Undocumented Student Task Force” focused on identifying barriers and developing solutions. Another—a private institution located in Massachusetts—created a list of alumni who are willing to offer legal and social service support to undocumented students and their immediate family members. This institution also fully covered undocumented students’ health insurance. Due to strong institutional support, the net cost of yearly attendance for the undocumented students was between $1 and $4,999. However, not all institutions have the resources to be able to serve undocumented students in this capacity. For instance, another private institution in Massachusetts reported admitting undocumented students and providing financial aid of $35,000 or more but the net cost for the student was still $20,000 or higher.

Of the responding institutions that admitted undocumented students, 52% reported providing financial aid. Financial aid in this case includes in-state tuition, grants or scholarship. A majority of colleges and universities offer institutional grants and scholarships (Figure 3), with some in Connecticut and Rhode Island relying on in-state tuition. Both responding Rhode Island public institutions provided financial aid in the form of in-state tuition. Of two Connecticut public institutions that provide financial aid, one offered in-state tuition while the other provided foundation-funded scholarships such as TheDream.US aid program. Conversely, no public institutions in Massachusetts provided financial assistance to these students.

Figure 3: What Financial Aid Is Available For Undocumented Students? (Aid type, # of institutions)

Note: Responses are not mutually exclusive.

Overall, the survey results shed light on the powerful impact of institutional leadership. Absent affirmative legislation or state policy in Massachusetts, individual institutions have taken it upon themselves to provide support for undocumented students. A subsection of Tufts University’s admissions page is specifically geared towards undocumented students, stating that “undocumented students, with or without DACA, who apply to Tufts are treated identically to any other U.S. citizen or permanent resident.” Recognizing that undocumented students are ineligible for federal financial aid, Tufts provides institutional financial aid, meeting 100% of the demonstrated student need. While not all institutions make information available online, often, private nonprofit institutions do assist undocumented students by providing institutional aid and connecting them with private scholarships. While this is admirable, not every institution has the financial means to support undocumented students. Given such disparities, legislation plays a crucial role in bridging the gap to ensure all qualified students have access to quality higher education.

The face of DACA

Faustina was fortunate to have the support of her school counselor. “She was determined to send me to college … you are going to college.” she said. She gave me hope which was something that I needed most at the moment.” Faustina’s school counselor was unwavering in her support—contacting everyone from her personal friends to people in the mayor’s office. Fortunately, Faustina was able to receive support from Clark University and plans on enrolling in fall 2017. Even with a college acceptance in hand, Faustina’s concerns about affordability are far from over. “Now that I am about to attend Clark, my only concern is finding a co-signer for my loans. I am still waiting to hear back from scholarships but so far I have a gap of $12,510 per year which is not bad considering my circumstances.”

“I am not embarrassed to tell people my immigration status because at the end of the day, I know that it does not determine my future or who I am. There is always going to be another way to reach my goal and get a higher education.” Faustina hopes to pursue actuarial science or computer science, at Clark. “I am just grateful to get the support that I needed from people who wanted to help [and] give me a chance at life and higher education.”

Faustina’s story is that of resilience and hope. Students like Faustina are the future of New England —we need to continue doing our part in making the higher education dream a reality for all students. While institutional leadership will continue to play a large role in enrolling, retaining and graduating undocumented students, state policy or legislative action is crucial to laying the foundation for extending financial support to these students.

Pooja Patel served as a policy research intern at NEBHE during academic year 2016-17 while she pursed her master’s degree in education from Boston College. This the final installment of her two-part series on undocumented students’ access to higher education in New England and beyond. To read part one, Are DACA Students Still Safe to Stay?, click here. For questions or comments, please contact Candace Williams at cwilliams@nebhe.org.

[ssba]